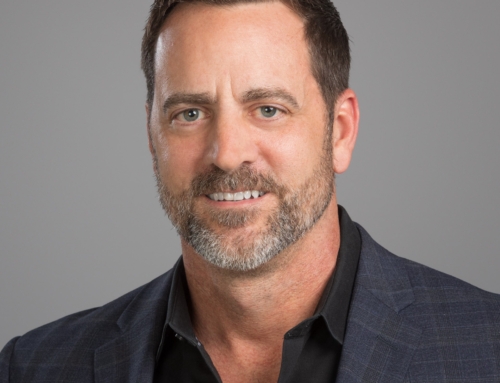

Jonathan Loiterman is an attorney, writer, speaker, and cannabis entrepreneur. Mr. Loiterman received his JD/MBA from Loyola University of Chicago and spent nearly a decade defending medical malpractice, as well as pharmaceutical and medical device product liability cases in Chicago. In 2014, he left his law practice to found Green Star Growing, Inc., an Oregon-based cannabis cultivator, processor, and wholesaler. Along the way, he participated hands-on in the licensing processes in both Illinois and Oregon, moving his family to an outdoor cannabis farm in rural southern Oregon.

Mr. Loiterman has served as a past Chairman of the Illinois State Bar Association Health Law Section and a past member of the Rules Advisory Committee for the Oregon Liquor Control Commission.

Thank you so much for doing this with us! Can you share with us the story about what brought you to this specific career path?

I got started in cannabis in 2013 when I served as the Chairman of the Continuing Legal Education Committee for the Illinois State Bar Association’s Health Law Section. That year, Illinois passed the Compassionate Use of Cannabis Pilot Program Act, and so my responsibility was to educate lawyers in Illinois about the program.

In assembling a seminar on the topic, I learned everything there was to know about Illinois’ new law and the history of cannabis legalization in the United States. It struck me that the Illinois program was a fulcrum point in the history of cannabis law in the U.S. The legislation was the first of its kind in the Midwest and one of the first in the U.S. to be passed by the legislature instead of a ballot initiative. I saw an opportunity to participate in something truly historic that had the power to address some of the injustices of the prohibition era, support economic growth in agricultural communities, and usher in the 21st century of agricultural technology.

Like many lawyers, I found law firm life to be very confining. Many young people don’t know this, but being a lawyer, even a litigator, is nothing like what you see on TV. A good chunk of a litigator’s job is having the same technical, procedural fights over documents, experts, and evidence with the same opposing counsel and the same judges over and over again, tracking every minute so the firm can bill for it.

Like many cannabis industry professionals today, we are at the vanguard of a multi-billion-dollar industry, writing the rules as we go along. I found the opportunity to be a part of that irresistible. It doesn’t hurt that I love rural life in southern Oregon too.

Can you share the most interesting story that happened to you since you began leading your company?

I think we’ve had a really interesting history with the government, in particular, the huge swings in the legal environment between 2015 and 2018.

The cannabis industry combines some of the wild-west mentality that drives the tech sector in Silicon Valley, but the regulations are incredibly tight for an industry in its infancy. As a result, you get a high level of friction with the government.

I think the cannabis industry is a useful lens through which to study the impact of regulation on business. Our story doesn’t tell the whole story, of course. Still, I think it highlights a significant problem of rules that are crippling to the kinds of small, independent businesses policymakers say they want to support. Often as not, these regulations not only fail to achieve the intended policy goals, they actively undermine them.

The voters of Oregon passed Measure 91 (a ballot initiative to legalize cannabis) in the 2014 election, and I moved there to begin operating a medical grow in the spring of 2015. Measure 91 was just a few pages of simple rules, and so we made our initial plans – and capital investments – based on that framework as well as what had already been in place for medical cannabis since the 90s. Using the past as a guideline for the future proved to be a tragic error because the legislature, various state regulatory bodies, and county and city governments each created entirely new packages of rules. A lot of new rules were in conflict with one another or were internally inconsistent; they were implemented on arbitrary timetables and repeatedly amended, often on an emergency basis.

It’s hard to overstate the impact all of this had on our business and many, many others, but I’ll share one brief anecdote about one issue. I think this story illustrates how the unintended consequences of regulation can completely undermine the intent of the rules.

It’s hard to overstate the impact all of this had on our business and many, many others, but I’ll share one brief anecdote about one issue. I think this story illustrates how the unintended consequences of regulation can completely undermine the intent of the rules.

In a nutshell, the old local government rules for medical cannabis allowed cultivation and processing facilities to locate in certain zones that would ultimately be forbidden under the recreational program. As a result, a lot of businesses found themselves unable to transition investments and infrastructure developed under the medical program to the recreational program. At the same time, medical retailers fled to the recreational program (which could not be dual-licensed), decimating the retail market for medical producers. Without getting too much into the arcane details of Oregon land use law, it turned out that local governments were mostly powerless to avoid this result. The statute changed the definition of a “farm crop” to include cannabis. While this allowed cannabis farmers to enjoy certain tax and legal protections afforded to producers of “farm crops”, it also meant that certain zones where medical cannabis was permitted that did not permit “farm crops” could not be used for recreational cannabis.

The net result for us and many others is that real estate and capital investments worth more than $1 million in the medical program were unable to be used in the recreational program. We found ourselves trapped in the medical program at a time when the number of medically licensed retailers plummeted about 90% in the span of two weeks.

We only survived by finding a way to secure two new sites for our operations. Starting over with new land forced us to the back of the line for licensing, while bureaucratic delays in the licensing process froze us out of the recreational market for another year and a half. If we built our facility on the other side of the road or if our property had not been a part of a failed re-zoning project from decades ago, none of this would have been an issue for us. We are among the lucky ones who survived this transition; many businesses were crushed or gave up and went back to the illicit markets.

From a community and a policy standpoint, the results were awful. Since our occupation of those facilities was no longer economically viable, we were forced to abandon the assets. Worse, the subsequent occupants there proceeded to deploy those assets to produce cannabis illegally immediately. Because that property was so remote, no one complained, and nothing was done to stop it.

It’s not hard to look at this and see that the policy result was that the government put a gun to our heads, stripped the company of a seven-figure investment in a state of the art cultivation facility, and turned it all over to the bad guys who don’t pay taxes and don’t follow the rules.

At the same time, you can’t blame the people in the Oregon government. They do an extraordinary job of managing impossibly complex problems with too little time and too few resources. Legislators, regulators, and local government officials are all operating in a world were too many pre-existing rules layered on top of one another produce a lot of absurd results. In particular, Oregon’s Governor Kate Brown and the executive director of the Oregon Liquor Control Commission, Steve Marks, have really shown courage and leadership on these tough challenges. We’ve taken our lumps as a business, and the regulators have encountered a lot of set setbacks. Still, I think Oregon has leveraged its cannabis industry for economic growth and tax revenues smarter and more effectively than just about any other state in the country. Oregon produces some of the best AND some of the lowest-cost cannabis in the world. The state is also laying the groundwork for industry leadership in the 21st Century.

I guess the moral of the story is that getting cannabis policy right is harder than most people realize, and a lot of states will struggle with the various trade-offs that are required to make legalization happen.

Can you share a story about the funniest mistake you made when you were first starting? Can you tell us what lesson you learned from that?

Back in 2015, it was a lot harder to find employees with demonstrable, verifiable credentials. Outside the cannabis industry, you might look at where someone went to school or what jobs they had previously held to get a sense of whether someone could fit into the role we had in mind. But those types of credentials were often meaningless to us in 2015. Back then, most of the best cannabis workers in rural Oregon had no university education. Few established and reputable firms existed that were operating commercially, so it was tough to assess anyone based on their prior employers’ reputation too. For us, it meant that we relied on word of mouth reputation to make a lot of early and urgent hiring decisions.

Unlike today, much of the Oregon medical program was a circus in 2015. Oregon hosted more than 30,000 registered medical cannabis growers, and their production of processed or extracted cannabis was almost entirely unregulated. In those days, the medical program had no site inspections, no testing, no inventory reporting or tracking, no financial transparency, no background checks for owners, no pesticide standards, and almost no enforcement of the few rules that were in place. The old medical system produced a lot of high-quality products at no cost for patients and veterans around Oregon. It also nurtured some of the best cannabis producers in the world, but the program created reckless and irresponsible behavior from people who operated well outside of business and legal norms.

From the grower who claimed he didn’t know it wasn’t OK to suck from a flask of whiskey all day, to the trimmer who stole one of the farm cats, to the manager who hired a shadowy network of his own indentured servants as employees of the company, to the lab worker who accidentally launched a highly-pressured wad of raw cannabis oil into the air: I saw a lot of pretty crazy things that first summer here.

We could have avoided many of those issues with more rigorous hiring and a better on-boarding processes—similar to what we use today. The lesson for me was that, although I came up in the world of “move fast and break things,” that philosophy can really lead you astray in the cannabis business.

Are you working on any exciting projects now?

We think there’s a lot of really great vaping hardware in development around the world. I can’t talk about who the potential partners are, but we’re looking carefully at working with some really solid manufacturers to provide Oregon consumers with the best vaping experience known to science.

None of us are able to achieve success without some help along the way. Is there a particular person who you are grateful towards who helped get you to where you are? Can you share a story?

In my case, there are far too many people to list here who’ve supported me professionally. It’s worth mentioning that I raised money from more than 60 different investors and relied on many informal advisors to get started in this business, and so there’s a story behind every one of those relationships. I’ll take this opportunity to credit someone in particular who passed away earlier this year: Dr. Herbert Sohn.

Herb was a triple threat: an MD/JD/MBA who practiced as a urologist, lawyer, and health care policy expert well into his 90s. I met Herb through my work with the Illinois State Bar Association. Among many things, knowing him was a rare opportunity for me to work as a peer with a member of the World War II generation – when I was still under 40 years old. I found his practical optimism and can-do attitude both inspiring and infectious. A few years ago, Herb was instrumental in drafting and advocating for an update to the Illinois Statutory Short Form Power of Attorney. The law made it simpler for patients, families, and health professionals to respect the health care wishes of those who become unable to make decisions for themselves.

Herb was the kind of person with the vision to build things big enough and to invest in things long term enough that he would not live to see the promise fulfilled. He was someone I turned to often and someone who was always steadfast in supporting me. His tireless devotion to the projects and causes he worked on is something that has inspired me to endure all the chaotic ups and downs of running a cannabis startup.

This industry is young dynamic and creative. Do you use any clever and innovative marketing strategies that you think large legacy companies should consider adopting?

We’re entering a time when certain old-fashioned, traditional things are becoming new again. In the attention economy age of Fyre Festival, Instagram influencers, and the like, I think people find simplicity, transparency, and authenticity to be fresh and compelling.

The simple truth is that value is viral.

You see many giant cannabis companies in the media talking about all kinds of big ideas and initiatives for changing the world. You see a lot of vanity celebrity products, as well. Those folks talk less, if at all, about their products and how those products deliver real value for customers.

I think today’s cannabis consumers are savvy and tune out the expensive marketing talk. Today’s consumers want value.

Our flagship product, Green Star Naturals™, is about providing the most authentic and wholesome cannabis vaping experience possible with no compromises. Naturals™ is 100% cannabis and has zero additives, flavors, or fillers of any kind. We source every Naturals cart so that we make each cart from a single strain grown in a single location. We use only supercritical CO2 extraction, avoiding the potentially harmful impurities that can occur with hydrocarbon-based extraction like butane and propane.

We get buzz in the cannabis business because we offer a clear and simple value proposition at an affordable price. Our customers want to enjoy the full flavor, experience and terp profile of whole flower cannabis with the mess-free convenience of a vape, and they don’t want that experience compromised by potentially harmful additives or impurities, plus they don’t want to pay $50 or $60 a gram.

Working hard every day to produce quality, wholesome products at an affordable price isn’t as sexy as, say, hiring Spike Jonze to make a viral short film about us, but it’s the kind of thing that delivers tangible value to our customers in every gram of our Naturals™ oil.

Can you share 3 things that most excite you about the Cannabis industry? Can you share 3 things that most concern you?

Most Exciting:

- Undiscovered potential – The scope of the applications for the cannabis plant are only beginning to be understood. Medical and commercial applications people have scarcely dreamed of are on the horizon.

- Growth for rural America – Cannabis has the potential to be a high-growth industry that benefits rural American communities in a way that tech and internet-based growth cannot.

- Laboratories of Democracy – It’s really interesting to see the diversity of policy choices in different states, and I’m hopeful that will lead to better policy choices down the road.

Most Concerning:

- Oligopolies – Many states, like Illinois, have chosen a path that is mathematically certain to enrich a tiny number of elite players at the expense of consumers and taxpayers there. Cannabis businesses can produce broadly shared gains but not when government stacks the deck in favor of the elite like that. Unfortunately, all the rhetoric about social equity in Illinois is just smokescreen for what amounts to a multi-billion-dollar giveaway. It’s tragic.

- Internal Revenue Code Section 280e – This is one of the biggest threats facing every cannabis business in the US. Cannabis businesses cannot take ordinary business expense deductions, meaning we get taxed on gross earnings instead of net. Fixing 280e should be a higher priority than it is.

- Patent Trolls – A lot of very broad claims have been submitted and approved by USPTO. Though it remains to be seen whether some of those claims will be enforceable in court, big chunks of the industry could be significantly disrupted by questionable patent claims in the future.

Can you share your “5 Things I Wish Someone Told Me Before I Started Leading a Cannabis Business”? Please share a story or example for each.

- “There are no solutions, only trade-offs.”

This is my favorite quote from the noted economist Thomas Sowell. I think it illustrates penetrating wisdom about really hard problems. Inside the package of things, you might to do to address any non-trivial problem, you will find the seeds for a new challenge.

Fundraising is an excellent example of this. Everyone would agree that having more cash will help you address a great many problems as a startup. But raising money to solve one set of problems will inevitably add financial headwind that frustrates the very goals you intended to support when you raised the money in the first place. When you raise money, you don’t really “solve” the problem of needing money; you trade that problem for the problem of owing money with interest or the problem of diluting your ownership.

That’s not to say there aren’t worthwhile interventions, just that there is no free lunch.

I think it’s helpful to think of in terms of the price of addressing a problem. This approach also helps set expectations that will help you get a jump on those second-order issues. Careful consideration of tradeoffs can help avoid situations where the side effect of the cure is worse than the disease: it happens more often than we realize.

- “If you are going to eat shit, don’t nibble”

This is a great quote from Ben Horowitz’ incredible book on start-ups, The Hard Thing About Hard Things.

Owning failures can be a powerful tool for building trust and understanding in organizations in counter-intuitive ways.

Early on, I pitched investors on a complicated proposal where I inadvertently included a significant error on a PowerPoint slide, overstating a key metric on the investment. I also re-iterated the error on the slide when I pitched people. In this case, we had to reach certain overall funding targets before anyone’s commitment became binding.

I discovered the error after we had received commitments just barely exceeding our target. Going back to the investors and identifying the error could have resulted in one or more people pulling out, blowing the raise and the six months of work that went into it and jeopardizing the objectives that motivated the funding. Failing to correct the error would have been unethical, but it would have been the easy thing to do.

I went back to the investors, pointed out my error, and offered to refund anyone if their opinion about the deal changed. Not only did we not have a single investor pull out, several investors actually increased their commitments.

While I committed an unfortunate mistake, owning it completely really gave me an opportunity to walk the walk of transparency and accountability, something that was a much bigger concern for these investors than one data point on one slide that none of them remembered anyway.

Reaching your goals will not make you happy or fulfilled, and that’s OK.

Reaching your goals will not make you happy or fulfilled, and that’s OK.

It’s really human nature to set goals and imagine a future version of yourself where the goal is achieved, and you are happy and fulfilled and ride off into the sunset: you’ve arrived.

But we know that really never happens. No matter how big the goal, success just sets the stage for a new goal. The process of achieving goals teaches you that the only path is the relentless pursuit of growth and learning, so the very skills and attitudes that led you to succeed in the first place will prevent you from being satisfied. There is always another mountain to climb

I’m someone who used to be a lawyer, specifically an associate at a firm with 50+ lawyers. Studies have shown lawyers are some of the most unhappy professionals you can find and there are some good, structural reasons for that. Certainly, there was a time when becoming a cannabis industry CEO was nothing but a hazy, fanciful notion I would imagine when riding the subway to court. It’s fair to say that this is my dream job.

It’s worth mentioning, though, that this isn’t my first or even my second “dream job.” When I was a 17, I worked as a video game tester for a few summers. When I was in my 20s, I briefly worked as a restaurant chef, and later on as litigator. As such, I’ve had the enormous privilege to reflect on what it means for me to live out a dream, outgrow that dream and go on to fulfill another.

The reality of becoming a cannabis industry CEO has surprised me and exceeded my expectations in a lot of ways. I’m enormously grateful for the opportunity, but it’s pretty far from riding off into the sunset. Even when you’re successful, running a company involves a never-ending stream of puzzles to deal with and so you can’t orient your personal happiness based on having fixed all the problems. You’ll just never get there.

I find the best path for me is to fall in love with the journey and the process. You have to learn to find fulfillment in the present; to reflect on all you have achieved and the obstacles you’ve overcome; to be thankful for and support all the really great people on your team who make everything possible.

I think this quote from Justin Kan, founder of Twitch, really captures the sentiment:

“I started a $1B company, but I have friends who started $10B companies, $30B cos. And those guys are looking up at Zuck, and that guy’s probably looking at Steve Jobs and being like, “I wish I was Steve Jobs.” And Steve Jobs is fucking dead.”

It can be really unhealthy to focus only on goals because, by its nature, goal-orientation will always leave you unfulfilled.

- Time management will be a top 3 challenge.

One of the things that’s really different about being a CEO is that my relationship to time has really changed compared to the other things I’ve done. As a lawyer, I tracked every activity in six-minute intervals because I had to bill clients and be accountable to my firm. There’s a pretty linear relationship between the work you’re doing and moving the needle for your clients and for the firm.

As a CEO, the question is more about how much impact you have than how much time you spend making that impact. You also end up spending a lot of time and being deliberate about choosing not to do things. So, you end up chasing a lot of dead ends: interviews with employees you don’t hire; meetings on deals that fall apart; projects you kill; research that doesn’t lead anywhere; investment prospects that go nowhere, and so forth. Add to that there that there are a practically unlimited number of leads to follow on critically important objectives.

In a situation where you can work yourself to death on a thousand things that don’t move the needle, the challenge really becomes more about making good choices about the highest leverage things to work on, balancing the risk that you’re on a dead-end path against the benefit of walking that path. Spending a lot of time on or getting really efficient at low-impact stuff is a trap that’s really easy to fall into.

- The biggest dangers are unseen, think about your blind spots.

Former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld infamously said,

“There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know. There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know. But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.”

I think it’s a useful way to think about organizational knowledge, which can be often be remarkably elusive. I would add to it, however, the unknown known: things that your organization or your team knows that you, as the leader, do not. A lawyer might call this “constructive knowledge” – a class of things you might be legally presumed to know even if, if fact, you did not know them.

As a health care litigator, I often would spend years deconstructing a few minutes or a few hours in exhaustive detail: interviewing every witness, reviewing every health record, examining every bit of historical residue of the underlying facts. The accounts never line up 100%. I found it nearly impossible to get multiple people – speaking truthfully to their attorney – to agree on the full details of, for example, a child’s birth (a circumstance I litigated many times). It isn’t always because people are manipulating, it’s because human memory and language are just not adequate to the task of rendering the truth of any past event in more than the most superficial detail.

The unknown known represents an untapped asset of unimaginable value. Many of your worst problems are hiding in things that are knowable but remain unknown. The important things don’t always rise to the surface, and sometimes you need to think strategically about what you’re mining for the unknown know at in the first place and whether you need to be looking someplace else.

What advice would you give to other CEOs or founders to help their employees to thrive?

I would advise founders to think of themselves as a coach and not a commander. Unless you’re supervising people, who are doing a completely mechanical task that has been perfected down to the tiniest degree, it’s really important to empower people to be their best on their terms. I think that means giving the people you trust the most the space to do things their way when you can and insist on detailed specifics only when you must.

You are a person of great influence. If you could inspire a movement that would bring the most amount of good to the most amount of people, what would that be? You never know what your idea can trigger. 🙂

I would inspire a movement for entrepreneurial education starting at the high school level, if not earlier. I think a lot of young people spend way too much time in school doing things like reading Shakespeare or learning about ancient Greek or Roman history. Those things are great – I certainly benefited from studying them – but if I had the choice of giving students an understanding of the greatest works of Shakespeare or a basic knowledge of how to start and grow a small business, I’d choose the latter.

While no one should consider me an expert in pedagogy, I think it’s fair to question the orthodoxy about what skills our education system deems essential for young people.

I’d love to have the opportunity to help young people learn about what’s possible for them.

What is the best way our readers can follow you on social media?

![“The potential to help people [in this industry] is enormous, but there’s still so much to learn.” – Ramon Alarcon, Witi](https://lakesideremedy.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/1thj5ekUyxQ69iLz1JJyODg-scaled-e1607882756286-500x383.jpeg)